|

Your call is not very important to us. By Zach Hively I recently had one of those customer service experiences that leaves one wondering if, possibly, the key to cracking all the world’s unsolved murder mysteries is lurking in those calls that may be recorded for training purposes. It all started because I decided to become a book publisher. I based this decision on the potential career earnings. Ha ha! I kid. I based this decision on the pleasure I derive from saying the words “book publisher.” Try it--book publisher. It’s a very pleasant phrase. But no book publisher is an island. It doesn’t matter how introverted I am; I have to rely on Other People unless I want to write all the books, and design all the covers, and harvest the timber to be pulped into paper all by myself. Actually, I do want to do all these things. But someone has to buy all the books to fund my book forest and my writing snacks. Which means customers. Which means … customer support. Now I don’t want to use names, so that if any customer support agents should go missing, I won’t be immediately linked to them. But the issue at hand, the reason I wrote to customer support in the first place, was that I needed to sort out a book problem with my distributor. A distributor, for those not in the industry, is a company that uses an ineffective, user-unfriendly, poorly designed, and ugly web interface to ruin all the metadata associated with a forthcoming book. And then—and then!—a distributor makes that ruined data impossible to fix because of reasons that do not apply. This corruption of data means the distributor cannot distribute this book to bookstores, which is a relief (for the distributor) because distributing books is outside their terms of service. That’s more or less what I wrote to the distributor’s customer support team three weeks ago, only I used Fake American Sincerity voice because at that point I had not yet waited three weeks for a response. I even tried to fix the problem myself first! More than one time! And then I opted to let professionals handle it so I didn’t wreck the rest of my week on a Tuesday. That was my first big mistake, assuming the professionals would handle anything professionally, or at all. I got my response two days later. The customer support agent also utilized Fake American Sincerity voice. The agent assured me, with text copied straight from some manual or other, of all the ways they had not read any portion of my plea for help. Because many of you are not book publishers and should not have to suffer through learning distributor lingo, I’ll translate the ensuing exchange into a more familiar context: Me: I would like some apples, please, because this is a supermarket. Customer Support Agent: According to this manual, we do not have broccoli. Me: But I just need apples. Customer Support Agent: You have allowed your carrots to expire. You may still eat them, but they will have a floppy mouthfeel. Me: Apples? Customer Support Agent: Potatoes are indeed delicious. I apologize for the dragonfruit’s inability to banana. Me: Will you understand “apples” better:

Customer Support Agent: No, but we will elevate your frustration to our advanced grocer team. I wish I were exaggerating. I am not. Yet the distributor had me bent over a promotional book display. I cannot distribute myself; this is one of those times I’m stuck relying on Other People. Maybe even Other AI Chatbots.

So I figured I’d try being patient for the book distributor’s advanced grocers to get to my support ticket. And I was patient, alright. I was patient for TWO. ENTIRE. WORK. WEEKS This put me nearly three weeks in, all told. At this juncture, I funneled anything else causing negative emotions in my life into a brand-new second support ticket. I asked the distributor (in transparently thin Fake American Sincerity voice) to give itself a suppository with an Encyclopædia Britannica. The response I got to that ticket kindly informed me that emails are answered in the order received, except for mine, which would be bumped to the back of the queue each subsequent time I wrote in asking for updates. Fortunately for the life and longevity of everyone involved, this response was a lie. (I might lie too, if my job were to answer last week’s support tickets on a Sunday night.) An advanced support team member informed me that the wrong and unfixable data could be fixed all along, just not by me. The team has also revoked all my data-editing privileges, including changing my own password. But this is okay! Because I have found a new career even more pleasing to say than “book publisher.” And I’m certain that grocers never have to deal with food distributors.

0 Comments

ESPANOLA, NM — Española Humane has temporarily closed its indoor dog kennel area to the public after routine testing revealed elevated mold levels in the ceiling. While the rest of the shelter remains fully operational, the dog kennels will remain closed during remediation efforts.

“We’re taking this seriously and moving swiftly to protect the health of our animals, staff, volunteers, and visitors,” said Kate Baldwin, Executive Director of Española Humane. “We’ve already brought in remediation experts, roofing contractors, and toxicologists to guide our response.” The decision, made out of an abundance of caution, comes after testing conducted on June 20, with findings interpreted on June 30. The shelter’s cat rooms, lobby, office spaces, and on-site clinic remain unaffected and fully operational. All services, including adoptions and veterinary care, will continue with adjusted operations. Thanks to the shelter’s short average length of stay for dogs, its indoor/outdoor kennel layout, and continuous airflow from fans, there is currently no indication that the mold has impacted the health of animals in care. Additional testing, including air and swab samples, is scheduled for July 9. Dogs and puppies are being relocated into temporary kennels outdoors as the organization prepares to purchase additional housing systems to maintain comfort and care during the remediation process. How the community can help: • Foster a dog – even short-term fostering helps • Adopt – lobby, cat, off-site, and outdoor adoptions continue as normal • Donate – help us build and outfit new kennel setups “We’re no strangers to tough situations—and every time, our community rises to meet the challenge,” Baldwin added. “Our mission goes on, and we’ll continue showing up for animals who need us. With your support, we’ll come out stronger.” Española Humane will reopen for public adoptions on Wednesday, with adoptions taking place in the lobby or outdoors. To foster, adopt, or donate, visit www.espanolahumane.org or stop by the shelter during business hours. ### Española Humane’s mission is to end animal suffering in underserved communities. We offer free spay/neuter, vaccinations, and work to build trusting relationships. To learn more about how you can help, visit espanolahumane.org. By Helen Byers

helenbyers.com [email protected] It was a spring afternoon in Medanales, and a gentle breeze was wafting through the screen door. I had just settled down at my drafting table when I heard it. Someone in the neighborhood was calling out. "Help!...Help!...Help!" It sounded deep, like a man's voice—but hoarse, a bit muffled. Then it came again, more urgently. "Help!...Help!...Help!" I rushed through the screen door, crossing the garden to the edge of the arroyo. There was no sign of anyone down there. Then where? On the other side of the arroyo? My mind flashed back to an early spring morning years ago, when I lived in a quiet town near Boston. I heard a man's voice calling for help, over and over, just like this. I rushed out, calling back, "Where are you?", and he could only respond, "Here! Over here!" I ran through a neighbor's yard to the next block up, and found the man in agony, sprawled on the frozen lawn of his wood-framed house, with a broken femur. He had been fixing a gutter on the roof, when the ladder slipped. ("What an idiot," he moaned. "I'll never do that again!") But what could be happening here, in Medanales? Various scenarios occurred to me: a guy pinned by a fallen tree, or a piece of machinery, or a farm animal? The possibilities were endless, maybe. I rushed back to the house and woke Ed up from his nap. "I think someone's hurt or in trouble! I think he's across the arroyo." Ed was up in a flash, and we were off down 142 in his car. We stopped first at Djann and Lisa's. Lisa was outdoors with a helper, working on a project of some kind. Had they heard someone calling for help just now? No, they had not, they said, looking concerned. Had we asked the Vigils, next door? We stopped there next. Three men stood outside. Had they heard anyone calling "Help! Help! Help!" a few minutes ago? They exchanged puzzled glances. No, but they would keep an ear out. Maybe farther down the road, or in the neighbor's field...? At the next stop, a woman was outdoors just beyond the gate. While Ed stepped out to ask her, I stayed in the car. Sitting there, I could just gaze off into the pasture beyond the fence, where there were cattle. t was there that I heard that call again, though this time louder. The same exclamation—urgent, hoarse, repeated three times—but not in human language. Then I realized: It came from no fellow. It was a cow's bellow. Northern New Mexico Pathways to Opportunity Strategy Table Announces Youth Fund Grant Recipients7/3/2025 Courtesy of LANL Foundation

16 Regional Organizations to Receive Over $1.4 Million to Support Career Development for Underserved Young People June 23, 2025 ESPAÑOLA NM – The Northern New Mexico Pathways to Opportunity Strategy Table proudly announces the inaugural round of Youth Fund grant recipients, awarding over $1.4 million to 16 regional organizations committed to expanding career pathways for underserved young people. The Northern New Mexico Youth Fund, launched earlier this year, is the first pooled fund of its kind in the region, combining philanthropic, tribal, state, and federal resources to support equity-driven Career Technical Education (CTE) and Work-Based Learning (WBL) programs for young people ages 13 to 29. These programs are designed to help underserved young people – especially Opportunity Youth, Native American youth, young parents, and others facing systemic barriers – gain the skills, confidence, and opportunities they need to succeed. The Youth Fund is a collaborative effort spearheaded by the Northern New Mexico Pathways to Opportunity Strategy Table, a coalition of 17 local, regional, and national partners coordinated by the LANL Foundation. Contributions from 12 funding partners now total $1.6 million, including approximately $1.1 million in philanthropic investments and $500,000 from the New Mexico Department of Workforce Solutions, which are administered by the New Mexico Community Trust. Through a participatory grantmaking process that engaged underserved youth, funders, and community leaders, the Youth Fund selected 15 CTE/WBL projects and one regional resource hub from a highly competitive pool of 35 proposals submitted by nonprofits, schools, tribal entities, and youth-serving organizations from across Northern New Mexico. “The launch of the Northern New Mexico Youth Fund is the realization of a dream many years in the making. It’s incredible to see so many like-minded partners come together to align not just funding, but a shared vision for investing in our region’s most valuable resource – our young people – and the organizations that support them. This is more than a grant cycle; it’s the beginning of long-term, transformational work. We are excited to see the impact these grantees will have and to continue building the momentum to grow both the number of partners and the financial support for the Youth Fund in the years to come.” – Alvin Warren, Vice President of Policy and Impact for the LANL Foundation “At NMCT, we believe that when philanthropy centers equity and collaboration, transformative change becomes possible. The Youth Fund represents a powerful example of what it looks like when communities, funders, and young people co-create solutions. We’re proud to be part of this growing movement to invest in youth potential, cultural strengths, and long-term opportunity across Northern New Mexico.” – Marissa Magallanez, COO New Mexico Community Trust In addition to the programmatic grants, United Way of Northern New Mexico has been selected to serve as the sole regional resource hub, receiving a $100,000 grant to provide technical assistance, organize shared learning opportunities, and deliver capacity-building support for all grantees. The hub will help organizations implement programs effectively, strengthen collaboration, and secure additional public funding. “We’re beyond thrilled to receive this award—and even more energized about what’s ahead! As the Northern New Mexico Youth Fund Resource Hub, United Way of Northern New Mexico is honored to uplift and empower our incredible grantees who are leading the way in work-based learning and career technical education. Together, we’re building a movement rooted in collaboration, equity, and real opportunities for youth and young adults across our region,” said Cindy Padilla, CEO. 2024 Northern New Mexico Youth Fund Grant Recipients

The Northern New Mexico Youth Fund is supported by a diverse group of contributors, including the Anchorum Health Foundation, The Annie E. Casey Foundation, The Aspen Institute Forum for Community Solutions, The Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, The Davis New Mexico Scholarship, The New Mexico Department of Workforce Solutions, The LANL Foundation, The Taos Community Foundation, The Thornburg Foundation, TRIAD National Security, United Way of North Central New Mexico, and The W.K. Kellogg Foundation. Learn More about the Youth Fund Learn More about the Strategy Table About the Northern New Mexico Strategy Table The Northern New Mexico Pathways to Opportunity Strategy Table is a collaborative of 16 national and regional philanthropic organizations committed to creating brighter futures for all young people in Northern New Mexico. Formed in 2021, the Strategy Table works to ensure that underserved youth ages 13-29 have access to the skills, experiences, and connections they need to thrive. Our investments in education, pathways, and economic opportunities help young people facing barriers build confidence, secure meaningful employment, and create lasting change in their communities. Through collaboration, equity-driven investments, and a shared commitment to youth success, the Strategy Table hopes to build a future where every young person in Northern New Mexico has the opportunity to reach their full potential. About New Mexico Community Trust New Mexico Community Trust (NMCT) is a tax-exempt public charity created to work in areas not serviced by existing community foundations. NMCT provides financial, investment, donor, and grant management services for communities across the state along with back-office support for multiple community foundations in the state. For more information, visit nmctrust.org. The tax and spend legislation going through the U.S. Congress could reverse New Mexico’s raises for health care providers who serve Medicaid patients called “provider rate increases.”

The unsettled fate of the Medicaid provisions amid rulings against their inclusion by the U.S. Senate parliamentarian leaves New Mexico waiting to see what its fate will be as a state with a heavier stake in Medicaid than any other. In January, New Mexico started paying health care providers who serve Medicaid patients at 150% of the rate paid by Medicare, with the goal of providing more people primary, maternal and behavioral health care. Legislative Finance Committee Director Charles Sallee told state lawmakers on Thursday that the U.S. Senate’s version of the bill would require states to bring hospital rates down to what Medicare pays. “That would be another big hit,” Sallee said at the LFC’s meeting in Taos. “The hospitals just barely got this program up and running.” The expanded payments started going out in the last few months, Sallee said, and have helped stabilize rural hospitals in particular. But it’s “a big unknown” if those payments will be upended, he said. Sallee said his staff is researching a concern raised by the state Health Care Authority, which runs the state Medicaid program, that these payment caps would apply to other kinds of services like primary care, maternal care and behavioral health care. He said he has asked to meet with U.S. Sen. Ben Ray Luján’s office next week about the issue. New Mexico has allocated more than $2.2 billion for provider rate increases over the past couple of years, Sallee said. “That would go away,” he said. “So that has significant implications for our health care system going forward.” Sen. Linda Trujillo (D-Santa Fe) asked why the federal government cares if New Mexico pays higher rates, and whether it has anything to do with matching what states pay out. Sallee said yes, particularly in states like New Mexico that have expanded their Medicaid programs. “That’s the majority in Congress’ thinking: ‘Why should we pay so much?’” he said. Sallee said he expects to update state lawmakers again about the federal budget in July. While dozens of New Mexico acequias continue reckoning with damage from natural disasters over the last three years, they are making progress, according to officials helping them navigate multiple layers of bureaucracy.

Disasters like the Hermits Peak-Calf Canyon Fire near Las Vegas in 2022, along with the South Fork and Salt fires in Ruidoso and the Rio Chama Flooding in Rio Arriba County last year, resulted in damage to 150 acequias, according to Paula Garcia, executive director of the New Mexico Acequia Association. That amounts to about one-sixth of the state’s roughly 900 acequias. Garcia gave a presentation to members of the Legislature’s interim Water and Natural Resources Committee, which is meeting Tuesday and Wednesday in Las Vegas, a town of about 12,000 that continues to grapple with the aftermath of the Hermits Peak-Calf Canyon Fire, particularly when it comes to post-fire flooding and potential drinking water contamination. The presentation occurs as President Donald Trump’s administration mulls deep cuts to the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the potential end of disaster declarations that keep certain emergency funding streams flowing to individuals and public entities. It also comes after dozens of people were fired locally from the Natural Resources Conservation Service, a federal agency that funds emergency watershed repair and other programs acequias rely on. Last week, Western governors agreed to explore formalizing inter-state partnerships to address the aftermath of post-fire flooding, a concern they dedicated an entire panel to during the annual Western Governors’ Association conference in Santa Fe. Agriculture that relies on acequias in and around the burn scar remains largely halted more than three years after the Hermits Peak-Calf Canyon Fire, Garcia said, and every rainstorm brings the threat that acequias will flood or fill with silt that flows off fire-scarred mountainsides. But she said her nonprofit organization and state government agencies are making progress when it comes to finally untangling a complicated federal bureaucracy that was initially unfamiliar with acequias and is still inflexible when it comes to ongoing flooding. “I would like for FEMA to clean up the bureaucracy and red tape, but we’re managing it now,” Garcia said. One major hurdle acequias faced concerned upfront costs they must produce before work can be completed, Garcia said. Even though state or federal agencies reimburse most or all costs, even modest upfront costs are often insurmountable for the small, volunteer-led irrigation canals. As such, more than 100 acequias statewide have sought help from the NRCS’ Emergency Watershed Protection Program, Garcia said, largely because that program allows acequias to offload the paperwork to a local sponsor like a county or a local soil and water conservation district. Thanks to a partnership between FEMA and state agencies, the state Transportation Department has entered into agreements with about 70 statewide acequias, including 54 in the Hermits Peak-Calf Canyon Fire burn scar, to allow the DOT to remove debris from silted-in acequias. FEMA then reimburses DOT for the associated costs. About 67 Hermits Peak-Calf Canyon acequias also have pending claims with the FEMA office overseeing a $5.45 billion fund aimed to compensate victims of the fire, according to Garcia’s presentation. Garcia called on the state Legislature to find ways to help acequias pay the upfront costs and to formalize a system to remove debris from acequias. She also called on the state to create its own version of the Emergency Watershed Protection program, which is popular among acequias and also reliant on an agency undergoing staffing cuts. According to various reports, NRCS laid off at least 35 people locally. “NRCS is a really wonderful agency, and it’s tragic to see those cuts,” Garcia said. “I think there’ll be implications for these programs if those cuts continue.” By Peter Nagle 6/30/2025

This is the July newsletter. We took June off to travel to the Northeast for my wife Joy’s daughter’s wedding. What a wonderful day! While there we visited with other family and friends in New Hampshire, Vermont, and Mass, including the Cape. it was a very fun trip! So, how have things gone in the markets? Quite well actually. Equity markets are at historical highs. Bonds have held steady. Interest rates are largely unchanged. It sure seems time for the Fed to lower rates. The fear that Chmn. Powell has had is that the tariffs Pres. Trump introduced will re-accelerate inflation. There is a danger that could happen, and it’s too early to tell whether they will, but so far they have not. It’s less that 6 months though so vigilance is still the word around here. There are reasonable arguments both ways on this, and I won’t bore you with the details but it appears so far that the tariffs have not led to the end of the world as some of us feared. This is likely because the President wisely pulled well back from the extreme approach he initially took. If he had tried to force those extremely high tariffs on other countries, I think the markets would have gone in the opposite direction than they have. I think he figured that out and rapidly changed course. Looking forward, markets never go straight up so it seems reasonable that we’ll see a decent size correction sometime in the next 3-4 months. 10 - 15% is my guess. And they are scary when they happen. But this could actually present a good buying opportunity if it happens. So I would keep some powder dry for that probability. As I’ve said before, a balanced approach generally works best. I like annuities for a part of your portfolio - they’re guaranteed not to lose money, and they can either pay you for life, or build up in value. And they’re tax deferred! They have a lot of advantages for the right situation, which is what I help people figure out. Where they fit, they’re unbeatable. There’s a place for all kinds of investments in your portfolio. Diversification is a sound investing principle. But as we get older, investing conservatively becomes more and more important. Especially in these unprecedented times. **************************************************************************** I provide financial advice to individuals in our Abiquiu community at no charge as a way of giving back. If you have questions in that area feel free to contact me. I’ll do the best I can to help you sort through the issues. Peter J Nagle Thoughtful Income Advisory Abiquiu, NM 505-423-5378 (mobile) [email protected] Courtesy of Archaeology Southwest Guest post by Istara Freedom (May 24, 2023)—My name is Istara Freedom. Born in Arizona, I spent my first 12 years in the Southwest, in the Four Corners area, around what is known as Bears Ears and Moab, Utah. We moved to the coast, and many years later, I discovered the long history my mom’s family has in New Mexico. Growing up, I wasn’t very aware of my mom’s complete heritage or the long, complex story of her and other Indigenous and European—primarily Spanish and Basque—peoples in the making of the Southwest. At one point, I became aware that my mom knew she was part Pueblo. Once on a visit to Abiquiu and the Abiquiu Inn and bookstore, I was drawn to look at books specific to the village, and quickly noticed my mom’s family surnames were prominent in several books. As I got to know Abiquiu better, I learned about the village and the Pueblo, which I had no idea was as rich, dense, and layered with a story that was formed before this country even became America as we know it. This story is layered with Spanish colonists and Indigenous Tribes, both local and migrating, and part of the vast undertaking that formed New Spain, then New Mexico, a history not to be covered here. I now know that this complicated narrative is a huge part of my family, my story, and the creation of my DNA. On a trip to Abiquiu, I learned about the Pueblo de Abiquiu Library and Cultural Center, and I began in-depth research with the extensive records collection there. In time, I got my mom to submit her DNA for analysis, which showed an unsurprising combination of about two-thirds Spanish and one-third Native American. One Abiquiu visit coincided with talks being given on New Mexico genealogy and a specific DNA study of Abiquiu residents, for which I was able to submit my Mom’s DNA. The studies indicate that her mtDNA comes from the Pueblo people, meaning that her earliest known female ancestor on this continent was likely of Pueblo descent. As it turns out, my family line, originating with the Spanish colonists, spent over 150 years in Abiquiu and surrounding areas in Rio Arriba County. I learned the term Genízaro, as well as how to pronounce it—heˈni zaɾo. Abiquiu is defined as a Genízaro village. Genízaros include individuals from many Native American Tribes enslaved by Spanish colonists or by other Tribes during raids and skirmishes. “They are living heirs to Native American slaves. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Native American women and children captured in warfare were bought, converted to Catholicism, taught Spanish and held in servitude by New Mexican families. Ultimately, these nontribal, Hispanicized Indians assimilated into New Mexican society.” (All Things Considered, NPR, 12/29/2016) The village of Abiquiu is located in Rio Arriba County. In every direction, there is evidence of human habitation and remnants of Indigenous and Pueblo peoples layered and dispersed in the cliffs, the hillsides, and even the village—both ancient and with some modern additions, such as Bode’s General Store and gas station. The ancient pieces of human history constitute an incredible timeline of continuous habitation for unknown millennia, from mesa top agriculture, cliffside pit houses, old Pueblo dwellings, and defensive natural fortress areas used by strong Native warriors to protect themselves from marauding Tribes and later, the Spanish settlers. My ancestors were probably on both sides of these conflicts. The Rio Chama runs through the entire area of Abiquiu, alongside US 84, and crosses under it through Barranca. Whenever I have seen the Chama, I have felt a definite yet indefinable emotion. It made more sense when, in the course of my research, I came across a record of a petition for land along the Chama by my great grandfather in the early 1800s. Although I could not find any records of an outcome to the petition, I can only imagine the dire importance of this water to my ancestors and all peoples who lived in these areas since the beginning of human habitation. In the Merced del Pueblo de Abiquiu, there is a plaza, with the main features being the St. Thomas the Apostle Catholic Parish and more recent structures, including the Georgia O’Keeffe home and the tiny library that also houses the cultural center. Surrounding the plaza are residential dwellings from old and crumbling adobes to a modern, vintage mobile home. There are only dirt roads here, no street lamps, crosswalks, or signage. On some roads, there are cattle crossings, and in two places, there are Catholic Penitente Moradas, features that are specific to New Mexican Catholics, and two cemeteries, one primarily for the Pueblo, and one for the village. The layering and the impacts of dwellings, reverence, warfare, detribalization, and settlement are dense, as it seems the dust never completely settled between events that happened here to make it what it is today. At one point in my research, I found my ancestors lived at an archaeological site called Las Casitas near El Rito, New Mexico, a small town not far from Abiquiu. The adobe site of Las Casitas lies north of Abiquiu in the El Rito Valley. It was founded in the first years of the 1800s by my forebears along with other families. My family’s connection to the site has not been revealed previously, and the builder and residents were described just a couple years ago as unidentified (Snow 2020). The site was partially excavated and studied by archaeologist Herb Dick and a crew from the Museum of New Mexico, but has not been well reported (Dick 1959). My great granny Sotela Martinez, and great granddad Juan Pablo Romero lived at Las Casitas. His father, Lorenzo Romero (my great, great-grandfather), is listed in the 1850 census for the area. My great, great-grandmother Concepcion Lopez was also living at Las Casitas, along with other aunts, uncles and cousins. I visited Las Casitas with Paul Reed, who subsequently invited me to share my story in this post. Las Casitas is now part of the Carson National Forest, and it was a very strange feeling, like being in a family home that has been raided, without much left for the remaining family to recollect. I felt moved with emotion, distance, emptiness, and a wonder that is hard to describe. I feel the pangs of my forebears, as reflected in my life growing up and who I am today. At St. Thomas Parish, in Abiquiu, the annual Feast Day occurs every November. The procession begins in the Plaza, enters the Parish, then returns to the Plaza and finally moves to a private home on the Pueblo. A central aspect to this day is the young women and girls dressed in colorful attire, representing the young Indigenous women and girls that were marketed in the village of Abiquiu, allegedly saved or purchased by the Spaniards from warring Tribes and ransomed in the village marketplace for wealthy settlers to use as servants and wives. The resulting children are the ancestors of the local Genízaro community. Each of us that comes to the Feast Day for our Ancestors is here to learn, accept, forgive, and care for what was important to them. We come to recollect the beauty, understand the loss and sorrow, and protect the land. We come to soothe their collective pain, losing tribe, identity, and children, and fighting in so many wars. Now we are fighting to reclaim our understanding and our identity and to give honor, recognition, and life to those that gave us ours. Acknowledgments My inspiration for this work comes from my mom, Estella. My research has greatly benefitted from the scholarly efforts of several individuals who have been pursuing Genízaro history for many years, including Moises Gonzales, Bill Piatt, and Gary Medina Cook, among others. The recent book Slavery in the Southwest: Genizaro Identity, Dignity and the Law by Piatt and Gonzales has been most helpful. Gary Medina Cook’s recent film The Genízaro Experience is a wonderful exploration of Genízaro history and social identity. I also want to thank the Trujillo family and many other folks in Abiquiu for welcoming me. I was blessed to be welcomed to the Santo Tomas feast day by many residents of the Pueblo de Abiquiu. Sharon Garcia, librarian at the El Pueblo de Abiquiu Library & Cultural Center helped me in many ways with my research. Thanks to Paul Reed. Lastly, I want to thank Carmen López, Mayordomo of the St. Thomas Parish, for her permission, compassion, and embrace in reverence for our mutual Ancestors on sacred land in Abiquiu during the feast day ceremonies. Link to Istara's book on Amazon. By Inciweb

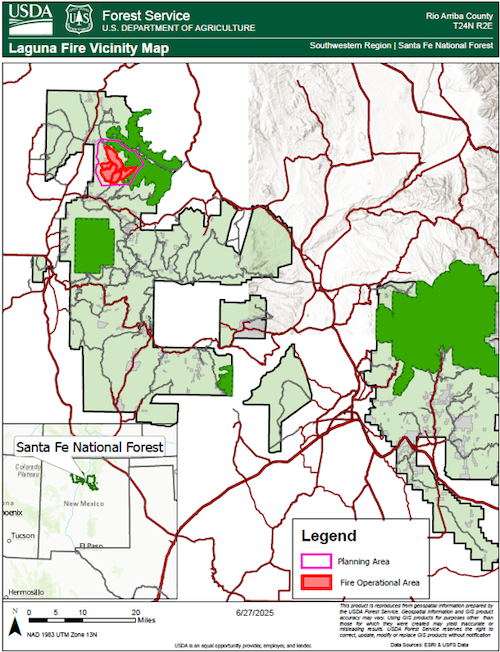

The 1300-acre wildfire is in the Coyote Ranger District Currently 10% Contained he lightning caused wildfire is 1300 acres and located in the Coyote Ranger District. It is burning in oak brush, Pinyon-juniper, and ponderosa pine. Aerial and ground resources are on scene. Low intensity surface fire has been observed with moderate rates of spread. Currently the Laguna Wildfire poses no threat to people or property. Crews will continue firing operations by hand to secure the fire's edge. To conduct a firing operation, firefighters cut away vegetation to make a line of bare soil ahead of a fire and then using aerial and hand ignitions burn the vegetation between that line and the actively burning fire front. Aerial ignition will be used to reduce fire intensity and to minimize firefighter exposure to ground hazards. Control lines being utilized include existing roads and natural barriers. The fire behavior is characterized as a low-intensity ground fire. Fuels being consumed include heavy dead and down wood, as well as tussock moth-killed mixed conifers. Tomorrow’s operations will remain the same. RemarksSmoke: Light winds today will push any smoke produced east and southeast of the fire this afternoon. Overnight smoke is expected to settle in the Rio Chama River valley, with the potential for some smoke settling along the NM State Road 96 corridor between La Jara and Coyote overnight, but no significant impacts are expected. On the 4th of July and Saturday, smoke may impact Los Alamos and Santa Fe but conditions are expected to remain at MODERATE levels overall. Heavy smoke is expected to settle in the Rio Chama valley overnight, along with potential impacts along the NM State Road 96 corridor but should lift in the morning. Individuals sensitive to smoke should take precautions such as closing their windows overnight. Safety: The health and safety of firefighters and the public are always the highest priority. Please avoid the area while crews manage the Laguna Wildfire. Drones and firefighting aircraft are a dangerous mix and could lead to accidents or slow down wildfire operations. If you fly, we can’t. Current Weather Weather ConcernsRain was heavier on the east side of the wildfire, and fire crews were not able to conduct firing operations Instead fire crews focused on improving holding features and access points. A helicopter monitored the wildfire from above, revealing that the fire was creeping and smoldering at a low intensity. On Wednesday, some areas exhibited heavy dead and downed wood, along with tussock moth-killed mixed conifers, which produced visible smoke. Location: The wildfire is in the Jemez Ranger District, near the northwest boundary between the Valles Caldera National Preserve and the Santa Fe National Forest, adjacent to Forest Road 144 and Twin Cabins Canyon.

Start Date: June 23, 2025, at 1:00 p.m. Size: 40 acres Containment: 10% Cause: Under investigation Vegetation: Burning in oak brush, ponderosa pine, and Douglas fir. Resources: 40 personnel Overview: Fire crews are actively managing the 40-acre wildfire using full suppression tactics. Currently, the wildfire does not pose a threat to people or property. Highlights: Fire line around the perimeter held overnight. This morning the wildfire reduced in complexity transitioning to a Type 5 incident. A Type 5 incident is the lowest level of complexity in incident management, typically manageable with minimal resources. Fire crews continue to mop up, which means extinguishing and removing burning materials near control lines. Currently, 40 feet from the fire line has been mopped up around the fire perimeter. Weather: Conditions will be mostly sunny and clear on Friday and Saturday, with showers and thunderstorms expected on Sunday and continuing into next week. Safety: The health and safety of firefighters and the public are always the highest priority. Please avoid the area while crews manage the Twin Cabins Wildfire. Drones and firefighting aircraft are a dangerous mix and could lead to accidents or slow down wildfire operations. If you fly, we can’t. Smoke: Smoke may be visible to communities along New Mexico State Road 96 and New Mexico State Road 4. Fire Information: Contact Claudia Brookshire, Public Affairs Officer, Santa Fe National Forest Phone: 505-607-0879 (available from 9:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.) Email: [email protected] Links: Santa Fe National Forest website, New Mexico Fire Info, Inciweb, and Santa Fe National Forest social media (Facebook and X). About the Forest Service: The USDA Forest Service has for more than 100 years brought people and communities together to answer the call of conservation. Grounded in world-class science and technology– and rooted in communities–the Forest Service connects people to nature and to each other. The Forest Service cares for shared natural resources in ways that promote lasting economic, ecological, and social vitality. The agency manages 193 million acres of public land, provides assistance to state and private landowners, maintains the largest wildland fire and forestry research organizations in the world. The Forest Service also has either a direct or indirect role in stewardship of about 900 million forested acres within the U.S., of which over 130 million acres are urban forests where most Americans live. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

July 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed